Autonomous Hacking of PHP Web Applications at the Bytecode Level

01/12/2023

Introduction

It’s 5th June 2022, after hacking on PHP’s Virtual Machine, I chose to experiment with an algorithm of my creation called the follow-back algorithm, aimed at automatically detecting vulnerabilities in the PHP codebase at the bytecode level.

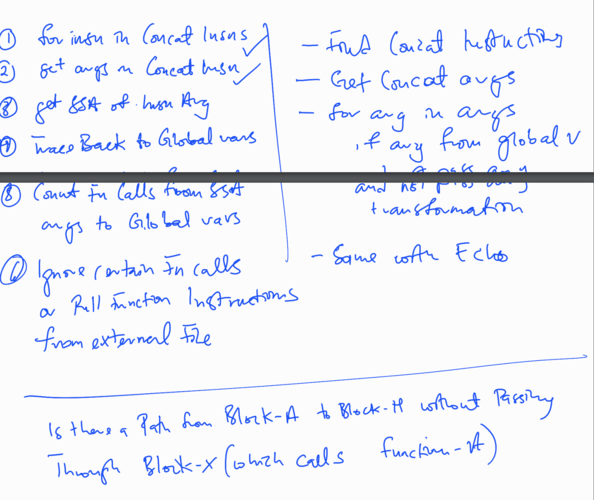

Left side of the image in text

1 - For instruction in CONCAT Instructions

2 - Get arguments in CONCAT Instruction

3 - Get SSA of Instruction argument

4 - Trace back to a global variable

5 - Count Function calls from SSA instruction argument to Global Variable

6 - Ignore certain function calls Right side of the image in text

Find [Concat, EHO] Instructions

Get [CONCAT, ECHO] arguments

for arg in arguments:

if arg can be traced to GLOBAL VARIABLE and

has not passed through any transformations:

it is vulnerable Following the research, I chose to assess it against the vulnerable web applications listed below. These applications are specifically designed for security professionals to enhance their skills and test their tools in a legal environment, serving as my test cases.

| Name | Vulns | Report | Github |

|---|---|---|---|

| Damn Vulnerable Web Application (DVWA) | 21 | Report Link | Github Repo |

| OWASP Vulnerable Web Application Project | 10 | Report Link | Github Repo |

| Simple SQL Injection Training App | 15 | Report Link | Github Repo |

| Vulnerable Web application made with PHP/SQL | 6 | Report Link | Github Repo |

| InsecureTrust_Bank - Educational repo demonstrating web app vulnerabilities | 5 | Report Link | Github Repo |

Additionally, I experimented with it on a few actual projects, and I plan to share the detailed report at a later date. Keep an eye out for updates on the reports by following me on Twitter @finixbit.

Common PHP Vulnerabilities

Before we delve into how the follow-back algorithm works. Let’s take a look at a few common PHP vulnerabilities. Most common PHP vulnerabilities get user input using global variables like $_REQUEST, $_POST, and $_GET and are later used in potentially vulnerable functions, generating SQL strings, echoing/printing back data to the user, etc. Example codes are below:

Generating SQL Queries

$sql = 'SELECT * FROM employees WHERE employeeId = ' . $_GET['data'] . $_GET['id'];Combining with other strings

$user = 'User: ' . $_GET['name'];

echo $userPrinting/Echoing out some data back to the user

echo "$_GET['p']";Include pages from user-supplied input

include $_GET['page'];Common Static Analyzers (REGEX Search, AST Pattern-based Search)

With the example codes above, vulnerabilities can be easily found using most static analyzers which are based on either AST pattern search or using regular expression search.

But gets tricky or incorrect if user-supplied inputs ($_REQUEST, $_POST, $_GET) aren’t directly used but travel across the different parts of the code before being used in potentially vulnerable functions like the examples below:

Example (1) code where AST pattern search analysis fails

$uname = $_POST["uname"];

$passwd = $_POST["password"];

$sql = "SELECT uname, passwd FROM users WHERE uname='$uname'";Example (2) code where AST pattern search analysis fails

$id = $_GET['id'] ?? 1;

$cusId = $id;

$anotherCusId = $cusId;

$file_db->query('SELECT * FROM customers WHERE customerId = ' . $anotherCusId)AST pattern search or Regex search static analyzers fail for the example codes above because user-supplied input is not directly used but passes through other user-defined variables before it’s being used which is a limitation for our analysis.

To be able to find the above vulnerabilities, you need to be able to track how data moves across variables down to where data is used in a potentially vulnerable function.

Overcoming the limitations of static analysis based on AST or REGEX pattern search

With the limitation of AST/REGEX pattern-based search, we need a way to track how user input data moves down to the designated sink function or instruction. This is where data-flow analysis comes in.

With Data-flow Analysis, you to track user input data defined in a variable down to specific destinated sink variables or instructions.

There are other interesting data structures like Control Flow Graph (CFG), Data Flow Graph (DFG), Static single-assignment (SSA) variables which are necessary for data-flow analysis.

But these data structures (CFG, DFG, SSA) cannot be extracted from a raw AST data structure unless the AST is broken down into a simpler Intermediate Representation or Instructions.

And PHP happens to have APIs (zend_compile_file) which translate PHP code/ASTs to its simpler Three-address code Zend bytecode instructions called opcodes and also APIs (zend_build_cfg, zend_build_dfg, zend_dump_ssa_variable) to compute the CFG, DFG, SSA variables information.

This got me excited because as someone who likes to perform a lot of program analysis on code, I always look out for frameworks and libraries which lift code from Code/AST to IR along with other data structure like Control Flow Graph (CFG), DFG, SSA, etc but in this case, PHP already had everything which also means no matter how complex PHP code is written, it gets reduced to 254 Three-address code instructions along with program analysis features.

PHP Bytecode Instructions

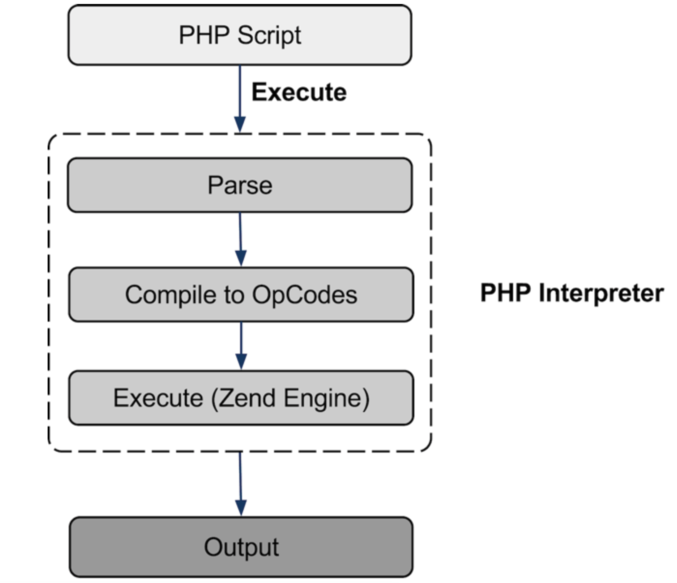

Since we working at the PHP bytecode level, we need to understand a few things about it.

PHP bytecode instructions are called Zend Opcodes and are generated by the interpreter and passed to the Zend Engine for execution.

PHP bytecode is a Three-address code memory-based instruction instead of register-based or stack-based which is designed to be executed and discarded with each instruction having a numeric identifier called OpCode which specifies which operation to perform by the Zend Virtual Machine. More information on PHP Opcodes.

Example Hello World code with its Generated Opcodes below using phpdbg.

<?php

$var1 = "hello";

echo $var1 . "world";

?>Generated Opcodes for the above Hello World code above

php@b4020519b49b:/src# phpdbg -p* test/test0.php

function name: (null)

L1-8 {main}() /src/test/test0.php - 0x7f70e0a6d300 + 4 ops

num opcode_name op1 op2 result

#0 ASSIGN $var1 "hello"

#1 CONCAT $var1 "world" ~1

#2 ECHO ~1

#3 RETURN<-1> 1Each instruction has an instruction index num, an opcode_name which is a string representation of its opcode number, 2 operands (op1, op2), and a return operand result.

We can see 4 generated bytecode instructions (ZEND_ASSIGN, ZEND_CONCAT, ZEND_ECHO, ZEND_RETURN) with their arguments. The list of OPCodes in PHP 7.

I like working at the instructions/bytecode level because it gives you granular information about how data is accurately moved in a program.

SOURCES and SINKS instructions or variables

To test my theory, we need to define the terminologies SOURCES and SINKS for our data flow analysis. The term SOURCES is where user input data is supplied and SINKS is destinated instructions or variables where user input might end up.

Source Example

FETCH_R instruction from the generated bytecode below fetches the global variable "_REQUEST" from op1 into a temporary variable ~0 in result and uses FETCH_DIM_R to retrieve "name" in op2 from temporary variable ~0 (op1) into temporary variable ~1 (result).

# User supplied Input data

$_REQUEST['name'];// Generated Bytecode Instructions for the above User-supplied Input data code

num opcode_name op1 op2 result

#0 FETCH_R<2> "_REQUEST" ~0

#1 FETCH_DIM_R ~0 "name" ~1Sink Example

ECHO instruction prints out data stored in op1 to the user. Even though in this particular example, op1 is "hello world", op1 can also be a variable which can be a user-supplied input data.

# destinated instructions or variables where user input might end up

echo "hello world";// Generated Bytecode Instructions for the above-destinated sink code

num opcode_name op1 op2 result

#3 ECHO "hello world"Understanding the follow-back algorithm

From the given SOURCE and SINK examples above, using the generated bytecode below we want to be able to track the temporary variable ~3 in op1 which is used in the ECHO instruction which is our SINK instruction back to FETCH_R and FETCH_DIM_R which are the SOURCE instructions where user input data is retrieved.

$var1 = $_REQUEST['name'];

echo $var1 . "world";// Generated Bytecode Instructions below

num opcode_name op1 op2 result

#0 FETCH_R<2> "_REQUEST" ~0

#1 FETCH_DIM_R ~0 "name" ~1

#2 ASSIGN $var1 ~1

#3 CONCAT $var1 "world" ~3

#4 ECHO ~3Once the sources and sinks are identified in our instructions, the next step involves extracting all variable arguments used at the potential sink instruction.

Afterwards, repeat the steps below until the current instruction is the source instruction that uses user-defined input.

1 - find out the instructions where these variables are defined using PHP’s Data-flow SSA APIs and set the current instruction to where these variables are defined

2 - retrieve all variable arguments (excluding constants arguments) used in the current instruction

3 - repeat step 1 if the current instruction isn’t our source instruction that uses user-defined input.

Manual walkthrough

Let’s manually walk through the follow-back algorithm using the simple vulnerable code below which gets user input from $_REQUEST['name'], stores the data in $var1 and prints it back to the user using echo.

$var1 = $_REQUEST['name'];

echo $var1 . "world";// Generated Bytecode Instructions for the vulnerable PHP code above

num opcode_name op1 op2 result

#0 FETCH_R<2> "_REQUEST" ~0

#1 FETCH_DIM_R ~0 "name" ~1

#2 ASSIGN $var1 ~1

#3 CONCAT $var1 "world" ~3

#4 ECHO ~3We start by pinpointing our SINK instruction, which, in this instance, is the ECHO instruction. The ECHO instruction accepts a sole argument op1 which holds a temporary variable named ~3, and outputs the content of ~3.

We need to find out where the temporary variable ~3 is defined and in this case, it is defined by instruction num #3 which is the CONCAT instruction.

Once we have where ~3 is defined, we can look for all arguments with variables used in the creation or definition of ~3.

The only variable used here is only $var1 in op1. Even though op2 holds data ("world"), it can’t be used because it’s a constant value and not a variable.

We now move to get where $var1 used in the CONCAT instruction is defined or created.

$var1 is defined at instruction num #2 which is an ASSIGN instruction.

We repeat the cycle by retrieving all arguments with variables used in the creation or definition of $var1.

The only variable used here is the temporary variable ~1 in op2.

We still repeat the cycle by getting where temporary variable ~1 is defined which is instruction num #1 which is a FETCH_DIM_R instruction.

So again we can retrieve variable arguments used in the definition of ~1.

The only variable used here is the temporary variable ~0 in op1 because even though op2 holds a data value "name", it cannot be utilized as it represents a constant rather than a variable.

the cycle is then repeated to find where temporary variable ~0 in op1 is defined, which is instruction num #0, a FETCH_R<2> instruction.

While repeating the cycle, we need to constantly check if we have arrived at our SOURCE input or instruction (FETCH_DIM_R, FETCH_R) and from the walk-through, we have arrived at the SOURCE input.

After accurately tracing back from a potential SINK to the input SOURCE, we can now retrieve the source code lines from all the recorded instructions along the paths and manually validate the Vulnerability.

Limitation of Follow-back Algorithm

Some variables are defined from function calls and the functions could be validators. This can be resolved by adding logic to record and check variables defined from function call instructions.

Also, some variables are passed as arguments to function calls which could return a new variable from the function return. This can also be resolved by adding logic to check if a variable is passed to a function call returns a newly created/defined variable.

This currently only works for PHP codebase which uses global variables ($_REQUEST, $_POST, $_GET) directly in all files but can be modified to use specific input instructions.

Other limitations are inconsistencies in DFG data structure from PHP probably due to incomplete code.

Source Code

The implementation of the Follow-back Algorithm can be found in php-bytecode-security-framework/detectors/code_injection.py, utilizing the finixbit/php-bytecode-security-framework.

Below is an illustrative scan of Damn Vulnerable Web Application (DVWA) is provided as an example using php-bytecode-security-framework/detectors/code_injection.py.

Refer to the README.md for instructions on configuring a test environment.

References

Some useful links to learn more about PHP internals and its opcode.